Stack vs. Heap: Where Your Code's Data Lives (And Why It Matters)

Ever had a program mysteriously crash on you? Let me tell you about the time I spent three days hunting down a bug that only appeared when my app had been running for exactly 37 minutes. The culprit? I didn't understand where my data was living.

Memory Management: The Haunted House of Programming

Look, we've all been there. You write some code that seems perfectly fine. It works in testing. Then suddenly in production, it crashes spectacularly. You run it again with the exact same input, and it works flawlessly. What gives?

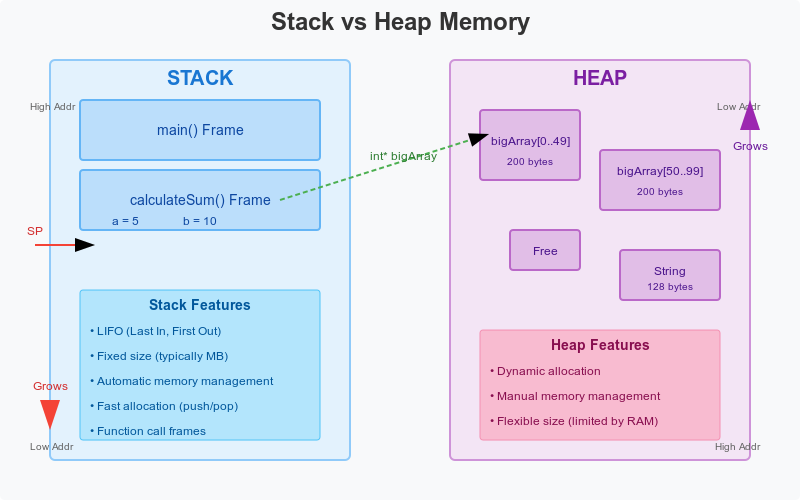

The issue often comes down to how computers organize memory. Your variables aren't just floating in digital ether—they live in two very different neighborhoods:

- The Stack: A Marie Kondo-approved apartment. Tidy, compact, with strict rules about what goes where.

- The Heap: That garage where your uncle keeps "everything that might be useful someday."

Let's pull back the curtain on both, with real code that I've actually written (and sometimes regretted). 👻

The Stack: Fast, Neat, and Kinda Small

The stack is where your local variables go to party. Imagine it like those spring-loaded plate dispensers in cafeterias:

- The last plate you put on top is the first one you'll grab (Last In, First Out).

- When you're done with a plate, it's gone immediately.

- Try to grab too many plates at once, and the whole thing collapses.

Here's some code I wrote last week:

#include <stdio.h>

void calculateTip() {

float bill = 42.54; // Lives on the stack

float tipRate = 0.18; // Also on the stack

float tip = bill * tipRate;

printf("Tip amount: $%.2f\n", tip);

} // All variables vanish here, like they never existed

int main() {

calculateTip();

// Try to access 'bill' here? Impossible! It's gone.

return 0;

}

When this runs:

main()gets its own little space on the stack.calculateTip()comes along and gets space on top of that.- Inside

calculateTip(),bill,tipRate, andtipare created. - When

calculateTip()finishes, poof — all those variables are instantly reclaimed.

Why I Love the Stack:

- It's wickedly fast. Like "blink and you'll miss it" fast.

- No manual cleanup means I can't forget to clean up (and I would forget).

- Perfect for all those little temporary variables I need.

Why the Stack Sometimes Betrays Me:

Last month I tried to process a 4K image pixel by pixel with arrays on the stack. My program crashed harder than my first attempt at parallel parking. The stack just isn't built for large data.

The Heap: Where Data Goes to Live Its Best Life

The heap is the Wild West of memory. Want to store an entire movie? Go for it. Want to keep data around after a function returns? No problem. But with great power comes... you know the rest.

Here's some code from a project where I needed to process a large dataset:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

// Need to analyze 10,000 sensor readings? Heap to the rescue!

float* sensorData = malloc(10000 * sizeof(float));

if (sensorData == NULL) {

printf("Well this is embarrassing... out of memory.\n");

return 1;

}

// Now I can work with massive amounts of data

sensorData[0] = 19.5;

sensorData[9999] = 20.3;

printf("First reading: %.1f\n", sensorData[0]);

// IMPORTANT: Return the memory when done!

free(sensorData);

return 0;

}

Here's what's happening:

- I'm asking the system, "Hey, I need space for 10,000 floating point numbers."

- The system finds a chunk of memory big enough and gives me the address.

- I can use this memory however long I want.

- When I'm done, I MUST give it back with

free().

Why I Turn to the Heap:

- It's the only practical way to handle large datasets (my image processing works now!).

- Data can outlive the function that created it.

- Memory size can be determined at runtime, not compile time.

Why the Heap Gives Me Nightmares:

Last year, I wrote a server that handled user requests. After about a week of running, it would gradually slow to a crawl. Classic memory leak—I was creating new heap objects for each request but occasionally forgetting to free them. Oops.

Under the Hood: How Memory Actually Works

Stack Memory: The Organized Bookshelf

Physically, the stack is a continuous block of memory, like a perfectly organized bookshelf:

- Each function call gets its own "shelf" (called a stack frame).

- These shelves stack perfectly on top of each other.

- The CPU has a special pointer (the stack pointer) that keeps track of the top shelf.

- When functions return, we just move the pointer back—no cleanup needed.

Heap Memory: The Cluttered Garage Sale

The heap is like a flea market where vendors (your allocations) can claim spaces of different sizes:

- Memory blocks aren't necessarily next to each other.

- There's a complex system to track which spaces are used and which are free.

- Finding space requires searching through available blocks.

- When you free memory, the system has to update its records.

A True Story: When the Stack and Heap Collide

A junior developer on my team (let's call her Sarah) once came to me with a puzzling issue. Her recursive function to generate Fibonacci numbers worked for small inputs but crashed with larger numbers:

int fibonacci(int n) {

if (n <= 1) return n;

return fibonacci(n-1) + fibonacci(n-2);

}

int main() {

printf("%d", fibonacci(50)); // Works fine!

printf("%d", fibonacci(10000)); // 💥 Stack explosion!

return 0;

}

What happened? Each recursive call adds a new frame to the stack. At 10,000 recursive calls, the stack couldn't handle it—like trying to stack 10,000 plates in a tiny kitchen.

We refactored her code to use the heap instead:

unsigned long long* fibonacciHeap(int n) {

unsigned long long* results = malloc((n+1) * sizeof(unsigned long long));

results[0] = 0;

results[1] = 1;

for (int i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

results[i] = results[i-1] + results[i-2];

}

return results; // The caller needs to free() this!

}

int main() {

int n = 10000;

unsigned long long* fibResults = fibonacciHeap(n);

printf("Fibonacci of %d: %llu\n", n, fibResults[n]);

free(fibResults); // Don't forget this!

return 0;

}

The code now:

- Allocates one big chunk of memory on the heap

- Uses iteration instead of recursion (no stack buildup)

- Returns the entire sequence for the caller to use

This version can handle much larger inputs without crashing, though we'd need bignum arithmetic for really large Fibonacci numbers.

How I Choose Between Stack and Heap

After years of debugging memory issues, here's my personal cheatsheet:

Use the Stack When:

- Working with small, temporary data

- Function-local variables that don't need to outlive the function

- Performance is critical

- You have limited scope

Use the Heap When:

- Working with large datasets

- Data that needs to be passed between functions

- Size is determined at runtime

- You need flexible lifetime management

What I've Learned the Hard Way About Memory

- Stack: Like a disposable camera. Fast, convenient, but limited.

- Heap: Like professional camera gear. Powerful, flexible, but you must maintain it.

The biggest mistake I see developers make (including past me) is trying to stuff too much into the stack. Just like you wouldn't try to store your entire wardrobe in your car's glove compartment, don't try to put massive arrays on the stack.

Your Turn to Play with Memory!

Here's a challenge I give to all my mentees: Write a function that intentionally crashes with a stack overflow. Then rewrite it using heap allocation to handle the same task without crashing.

Start with something simple, like a recursive function that calculates factorials or processes a deeply nested structure, then see how you can transform it to use heap memory instead.

PS: If you enjoyed this explanation, check out my next post where I'll dive into how garbage collectors automate heap management in languages like Java . Memory management doesn't have to be scary!